Methodology

Integrative Literature Review & Reflexive Thematic Analysis

A literature review (LR) is conducted to provide a snapshot of the research on a particular topic at a point in time. An integrative literature review (ILR) differs in two ways; firstly, the ILR allows material for analysis to be selected from a broader base including books and interviews; and secondly, the author’s role in presenting a novel interpretation of the material is deemed to be the purpose of ILR. The Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) also emphasises the author’s interpretive process, initially while identifying and selecting themes emerging from the examination of the literature, and later while performing the analysis of the literature using these themes as a focus.

Forty peer-reviewed studies were selected for this IRL. These studies use naturalistic stimuli, such as narratives, to produce patterns of activity within the Default Mode Network (DMN) which are examined using fMRI analysis. FMRI identified DMN as the region of the brain most active when the brain was in a resting state in 2001. The selected studies were all published after studies using naturalistic stimuli were revealed as having the greatest ecological validity, or real world implications, in 2008; 73% of the selected studies have been published since 2015, with almost half of these published in the last four years. In 2023 examination into the effects produced in DMN by naturalistic stimuli appears to be confined to the realm of cognitive neuroscience.

Three distinct, yet closely associated themes were chosen for the RTA. These themes, reflect the important functions of DMN, and support the proposal that DMN is central to the Concept Building Brain, facilitating the development of language; the Storytelling Brain enabling the efficient transmission of thoughts and emotions; and the Social Brain encompassing reflection, simulation and foresight. The selected studies expand on these themes and suggest they form an Evolutionary Triptych which formed the driver for human evolution. [GO BACK]

Findings of the Reflexive Thematic Analysis

The Concept Building Brain

Both narrative comprehension and effective communication requires accurate transmission of information, thoughts and experiences between individuals. Although this will depend on a shared understanding, knowledge and interpretation of the language and modality of a discourse, effective transmission of information will also depend on a shared meaning, or mental model, of the concepts and relationships within that discourse. This mental model is referred to as a “situational model”. FMRI reveals how the human DMN endeavours to maintain coherence in this situational model which is built from a multifaceted, multilayered, interrelated catalogue of concepts, which is itself being continually updated with incoming, and often conflicting, information—such as during the unfolding of a narrative. Naturalistic stimuli in the form of silent movies demonstrate not only that retrieval, updating and integration of information in memory occurs in DMN, but that DMN acts as a temporary location for incomplete information, synthesising new intrinsic and extrinsic information, and updating the situational model with this new information as it became available. Significantly, the process of creating and updating situational models—which includes creating relationships, generalising, updating and even nesting concepts—occurs within DMN in ways that are independent of both language and mode of delivery.

One recent study which found that relationships between concepts can be both widely distributed across DMN yet also located in overlapping areas, and nested but simultaneously generalised, proposed that concepts are encoded together with the relationships between concepts, and that DMN is central to the semantic processing of these concepts. Authors of this study also reported that activity in the dorsal attention network (DAN)—activated during focused attention—increased and DMN activity decreased as concepts became more concrete; and that left hemisphere activity was more likely to be associated with concrete concepts while the right hemisphere was associated with more abstract concepts.

Naturalistic stimuli includes narratives presented as printed matter, audio files, film, silent movies, and animation, but can also include photos used to prompt personal narratives, imagination or memory. Studies using naturalistic stimuli have demonstrated not only that DMN processes concepts in ways that are independent of language, but also that narrative processing activates regions of DMN associated with Theory of Mind (ToM), and that neither language nor mode of presentation impact on how DMN processes concepts and relationship between concepts. This final point suggests that DMN capability to store concepts, relationships, and relationships between concepts—a capability necessary to facilitate communication— possibly predates the development of language.

FMRI can monitor how complex concepts are processed both within DMN and over time. Although DMN activity is unrelated to language during comprehension, language is used to construct, integrate, relate and augment meaningful concepts first as words, then sentences, and then paragraphs during a “temporal receptive window” in which information is stored before being processed. This time lag—between processing and integrating complex ideas from the language processing areas, through the DAN and finally within the DMN—can be up to six seconds. During comprehension the sensory and language processing areas are deactivated as DMN is prioritised, and are reactivated when DMN resets at “event boundaries” (points of conceptual or perceptual change) in a narrative.

These studies from the field of neuroscience indicate the fundamental role of DMN in Concept Building, and thus narrative comprehension, as information from external stimuli is combined with existing memories and beliefs to create, refine, augment and update concepts and relationships between concepts, within DMN’s situational model, in ways that are independent of language. They show that narrative comprehension is a hierarchical process, with words and sentences buffered within DMN before being synthesised, nested or generalised into more complex concepts. Finally, they show that event boundaries in a narrative are associated with consolidation of concepts as the concept building DMN is deactivated and reset in preparation for generating or updating the next situational model. [GO BACK]

The Storytelling Brain

InterSubject Correlation (ISC) is a phenomenon, identified using fMRI analysis, in which brain responses to external stimuli are shown to replicate across individuals. ISC is the strongest evidence from neuroscience that emotional content in stories can be transferred from the storyteller’s brain to the brains of their audiences. Furthermore, indications that ISC corresponds to specific points in a coherent narrative suggests that regions of the human brain, such as DMN, are designed to respond to elements characteristic of stories. FMRI and ISC also identify patterns of activity linked with naturalistic stimuli indicating that DMN interacts with other regions of the brain, referred to as functional connectivity (FC). Furthermore, reading fiction has been shown to increase FC, which in turn has been linked to increased creativity and also increased resilience.

ISC patterns of activity in regions of DMN related to Theory of Mind (TOM) also confirm that prior beliefs and cultural influences affect responses to moral issues, interpretation of events, the lenience or severity of punishment, the subjective rating of comedy, and other emotional responses to naturalistic stimuli. Thus ISC and fMRI analysis confirms that narratives invoke a response directly related to personal perspective—and therefore a response from DMN—providing a neurological explanation of why each person’s interpretation of a narrative is unique.

FMRI analysis using naturalistic stimuli shows increased ISC within groups of participants with similar psychological outlooks and personality types, and with proximity in social media friendship circles. Not only does ISC confirm that naturalistic stimuli are processed within the DMN in ways that are unaffected by mode of delivery, but ISC also identifies a “strong social structure for DMN” independent of language.

ISC and naturalistic stimuli have demonstrated differences in DMN activity associated with problem solving styles, specifically holistic versus analytical thinkers. ISC showed that DMN activity in holistic thinkers was more strongly associated with regions related to moral processing and self-reflection, while ISC among analytical thinkers occurred more often in DMN regions associated with object and motion processing, and intentional and emotional mentalising. As thinking styles can be culturally related, these results confirm with empirical evidence that culturally diverse teams, study groups and friendship circles can benefit from cultural differences in problem solving styles.

ISC demonstrates how narratives improve consensus building and team coherence, also indicating that greater ISC, and thus more effective consensus within groups, occurred in groups having freer and more balanced distribution of members’ contributions to discussion. Naturalistic stimuli and ISC suggest that leaders are more supported by team members and teams are more creative and successful, when team leaders are allowed to emerge or be appointed by team members during a task. These studies also suggest, firstly, that narratives can be used to promote consensus, encourage effective discussion of ideas and reveal the best team leaders for creative problem solving; and secondly, that the process of appointing team leaders might be determined by the goals of the team—be they creative problem solving, consensus or productivity.

Studies investigating the role of the storyteller using fMRI and ISC have produced findings which suggest the role of the storyteller is significant for enhancing comprehension in their audiences; comprehension, indicated by greater ISC, is related to active engagement, prediction and thus successful communication. In a series of studies, ISC was found to be greater between storyteller and audience when the storyteller was retelling a story recalled from memory, or describing an event they were watching unfold, rather than reading a narrative. Greater ISC could indicate that the storyteller has tailored the story to their audience—evaluating the relevance of events and adjusting the complexity of details to assist comprehension. Once again, ISC occurred in regions of DMN which corresponded with the story’s social aspects and values. These studies found DMN also encoded information in regions related to the mirror neuron system (MNS), such as emotion, which is reactivated and transmitted during recall.

Naturalistic stimuli in studies focusing on ISC between individuals provides empirical evidence suggesting that DMN selectively encodes into memory the narrative elements, including emotional responses, which are likely to be most relevant or essential for successful transmission of meaning to others, either immediately or as part of a more complex story. ISC also provides empirical evidence demonstrating that narratives are processed within DMN in ways that generate social coherence, consensus, shared goals, and even identify the most unifying and effective leaders. In these studies neuroscience has provided empirical evidence suggesting that information shared as narratives promotes ISC which enhances effective communication and widespread understanding and thus supports the Storyteller role of the human DMN. [GO BACK]

The Social Brain

In 2001 DMN was identified as a network of brain regions most active during Mental Time Travel (MTT). MTT refers to the spontaneous and self-referential thoughts that occur when the brain is not focused on external activities. During MTT the DMN is unresponsive to external sensory input such as audio or visual stimuli. MTT emerges in early childhood, possibly in children as young as three years of age and it is estimated that an adult can spend more than 60% of their waking life thinking about the past or imagining the future.

It is the personal and social context of MTT which indicates the role of DMN as the Social Brain. Memories, plans, simulations and perspectives are self-referencing, therefore the DMN which is associated with introspection, self-projection, self-location and Theory of Mind (ToM) is strongly implicated in MTT. The temporal landscape of MTT varies; episodic memory engages MTT in revisiting the past while episodic foresight in the form of simulation, prediction and planning, takes place in an imagined future.

The purpose of MTT also varies and DMN interacts with other regions of the brain accordingly. Goal directed MTT, such as planning, problem solving or imagining future scenarios, are “supervised” by the executive and salience networks which evaluate thoughts for relevance and feasibility. Spontaneous thought chains are characteristic of “unsupervised” MTT”. Thoughts associated with weighing alternatives, or making moral judgments are considered to be “contextual” MTT while “non‑contextual” MTT occurs during REM. Non-contextual thoughts occurring in certain mental illnesses such as delusion and schizophrenia appear to be associated with poor FC between DMN and the executive and salience networks. Divergent thinking and creative problem solving, while associated with MTT, are related to high FC between DMN and other regions of the brain during MTT: however, the Aha! Moment (insight) is most likely to be associated with periods of MTT dominated by DMN exhibiting unique behaviours.

Skilled authors, aware that MTT is associated with engagement, transformation and immersion in a narrative, use literary techniques such as time and perspective shifts, conflicting or missing information, and fallible narrators to generate reflection, confusion and prediction errors, and invoke MTT in readers. Narratives invoke MTT which is externally guided as readers, prompted by the storyteller, imagine other worlds, step into the lives of other beings, and engage in self-reflection in ways that promote enduring personality change, and yet uniquely personal. MTT also informs the interpretation and understanding of essential literary elements such as metaphor and simile; it gives authenticity to simulations and predictions of events in fictional worlds; it facilitates empathy; and it engages with the MNS and the dopaminergic regions which register feelings of reward and punishment alongside opportunities to learn from the mistakes of others. MTT is considered to be an essential part of the reading experience.

MTT is responsible for increased deviation from, and a hindrance to the successful completion of, many tasks. However, many consider MTT, characterized by spontaneous and stimulus independent thought, as an activity unique to humans, important for maintaining the DMN in operational but “autopilot” mode during periods of boredom—a baseline level of arousal which facilitates optimal performance on mundane tasks. A study which investigated both these possibilities, using fMRI analysis and naturalistic stimuli, identified an inverse relationship between MTT (DMN activation) and focused attention (DAN activation) along a gradient (rather than a dichotomy). High DMN activity was found to produce faster and more accurate results at some stages of the test, while at other stages produced slower and more error-prone results. Although DMN activity associated with MTT generally produced poorer results, DMN activity was often linked to faster reaction times, better target detection, and practiced effortless performance associated with “flow” or “being in-the-zone”. A later study indicated that DMN/DAN activity was context dependant, determined by the saliency and predictability of incoming information; in predictable situations the DMN switched to autopilot mode and acted as a sentinel which contributed to rapid decisions based on predictions, best-guesses and learned information— important socio-emotional skills.

Studies which demonstrate that MTT can be associated with eye-blinking during a reading task provide insights into comprehension; as DMN is engaged for internal processing such as problem solving or comprehension, an eye blink coincides with the deactivation of the visual processing regions of the brain; the subsequent reengaging of these visual or audio sensors coincides with another blink. Naturalistic stimuli and fMRI reveals that MTT can play a significant role in conceptual learning, and blink patterns might indicate when this is occurring.

In 1986 Joseph Bruner described how readers of fiction inhabit landscapes of consciousness when engaging with characters, and landscapes of action when engaging with objects, scenery and actions. FMRI analysis of DMN patterns have shown that engagement with characters (ToM) and engagement with actions and scenery correspond to two distinct regions of the DMN during MTT. While participants might show a preference for one form of engagement over the other, researchers noted firstly that this preference was not mutually exclusive but rather was an inverse relationship along a gradient; and secondly that participants could shift between the perspectives of consciousness and action when prompted by guided questions. A more recent study, examining MTT as a function of engagement with characters using ISC, found that engagement with characters invoked greater ISC between participants than engagement based on action; that patterns of activation in DMN were related to the participants’ positive or negative engagement with the narrative’s characters; and that positive engagement with characters activated the dopaminergic network—the regions of the brain associated with reward and pleasure, error-prediction, surprise, risk assessment and creativity. This finding suggests that readers experience vicarious rewards and positive emotions alongside those of their preferred characters. In short, these studies suggest that targeted questions can encourage readers to engage with characters, and also that during positive engagement with characters the brains of readers are registering emotions related to reward and pleasure.

During MTT images relating to the future appear more vividly than images recollecting past events, suggesting that the main purpose of MTT is foresight and prediction. Additionally, near future events are more likely to be linked to areas of DMN associated with concrete concepts, while goals that are further into the future are associated with areas of DMN that represent abstract concepts. When asked to imagine future events, DMN activity indicated that MTT combines memories into future projections, and also that imagining potential future social interactions includes emotional and adaptive responses, once again suggesting that simulation, prediction and projection might be the chief function and purpose of the human tendency to engage in MTT. And while the definition of narratives can be applied to non-fictional accounts as well as fiction, participants are more likely to engage with fictional characters, consider their motives and emotions, and speculate about possible outcomes, whereas for passages labelled as non-fiction participants’ responses indicated that the outcome was seen as having already been determined since the narrative was understood to be describing an event that belonged in the past. Thus MTT, which facilitates comprehension, communication, creativity, social awareness and vicarious experiences, appears to be inclined towards foresight in preparation for the future.

FMRI shows that the processes of reading which involve simulation—including evaluating the behaviours and motivations of fictional characters, scene building and imagining future scenarios—recruit the regions within the DMN which correspond to vividness, social content and abstract concepts; that MTT involving simulations related to engagement with the social content within a fictional narrative enhances readers’ socio-emotional skills; and that greater reading frequency leads to greater FC which is linked to increased creativity, resilience and a broader moral perspective.

Thus, DMN role as the Social Brain can be demonstrated firstly by studies highlighting the self-referencing aspect of MTT which revisits and examines memories, emotions, goals, beliefs and relationships in a self-reflective process; secondly, by studies which indicate that the primary role of MTT is to recombine these past events into future projections, where memories provide a realistic basis for simulation, prediction, adaption and creativity, informing foresight and facilitating learning; and finally, by maintain an autopilot mode for DMN which facilitates rapid assessment of and response to both real and social environments. [GO BACK]

The Evolutionary Triptych

Discussion on the Reflexive Thematic Analysis

Investigating the actions of naturalistic stimuli on the human brain using the tools of cognitive neuroscience provides empirical evidence that the Concept Building Brain creates, updates and stores multifaceted concepts which include spatial, temporal and emotional content, including reward and pleasure, in processes which are independent of language. Moreover, while every individual brings a unique and personal set of past experiences and beliefs to the interpretation of a narrative, ISC indicates that specific attributes of those experiences and beliefs, such as emotion, are associated with particular areas of DMN, suggesting DMN also plays a fundamental role as the Storytelling Brain.

Studies examining ISC also indicate that narratives align participants who share common experiences and beliefs, but also provide vicarious learning opportunities to expand those experiences and beliefs, thus encouraging cultural diversity; and narratives can unite communities and reinforce social values by framing fictional events within established social and cultural mores. In addition, these studies highlight the importance of MTT in narrative comprehension, and the fundamental relationship between narratives and self-reflection, personality, personal goals and values, and the development of ToM. Neuroscience, therefore, provides empirical evidence of relationships between narratives and both self-referencing and social foundations of MTT, which suggests DMN acts as the Social Brain.

Thus, this RTA demonstrates the apparent tendency for DMN to make meaning, ensure social cohesion and nourish foresight, and suggests that the human DMN developed as an Evolutionary Triptych, comprising the Concept Building Brain, the Storytelling Brain and the Social Brain.

This ILR indicates the impact of stories on DMN–the regions of the brain associated with personality and behaviour– and invites further study into the role of stories in supporting educational outcomes and socio-emotional development in children. But this sample of studies which investigate DMN under the influence of narratives also provide empirical evidence of interactions between DMN and the dopaminergic system, the salience network, the executive control network and the dorsal attention network during narrative comprehension; interactions which could impact all aspects of personality and personal potential, including creativity, social interactions, planning, insight and self-perception, to name just a few. Therefore, the evidence showing how narratives guide positive and constructive MTT suggests that narratives written for young adults have the potential to promote adaptive behaviours, especially during adolescence when social and emotional factors are key motivators for learning.

It has been suggested that social selection, reinforced at least in part by narratives, has shaped human evolution, more so in humans than in any other species, and possibly more so than the forces of natural selection proposed by Darwin. It is not implausible then to suggest that the rapid pace of human evolution and the advancements in human intellect would not have occurred without stories.

[GO BACK]

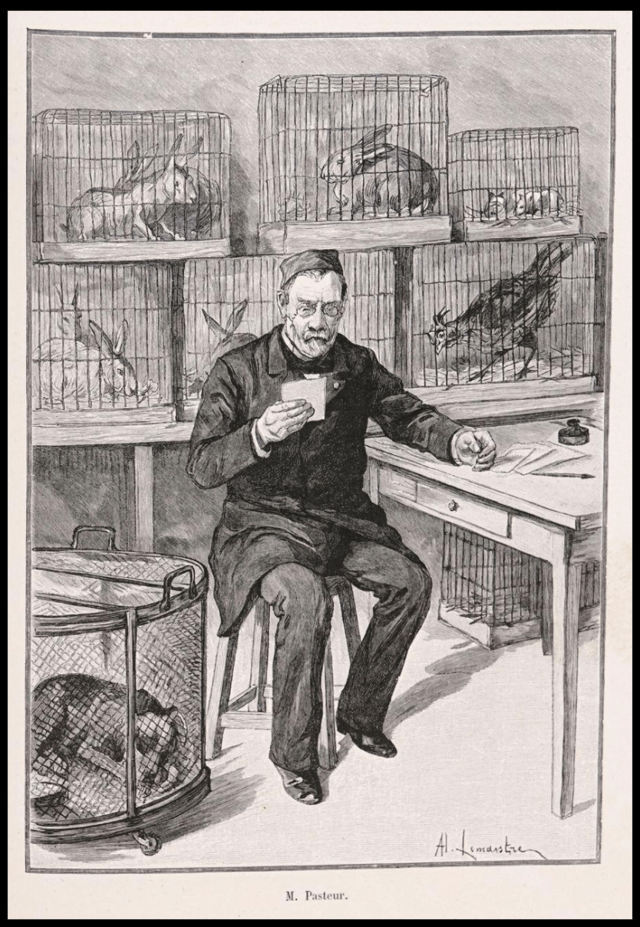

Photo by S O C I A L . C U T on Unsplash